The good thing about Blended Learning is there are many ways to do it.

The bad thing about Blended Learning is there are many ways to do it.

So while you are planning as a school, grade level, or a team to offer “Blended Learning opportunities” in classrooms, how do you know what others mean by Blended Learning? Do you anticipate parents, administrators, or your colleagues to have different ideas and therefore different expectations? Let’s talk about ways to clarify how you will “blend” instruction and how much online content to offer in your course.

Amount

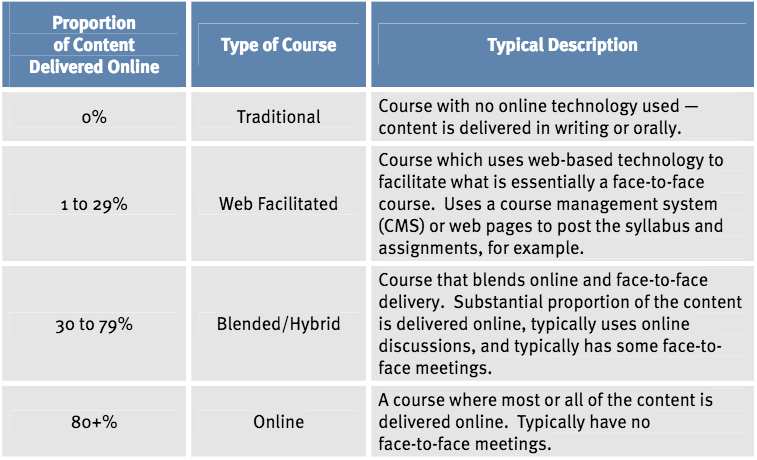

In 2007 The Sloan Consortium ( presently the Online Learning Consortium) asserted that when 30-79% of class content is available online that is a blended learning class.

Embrace this wide room to roam, it allows you as a teacher to do several things. You can still prepare with your colleagues for the uppermost amount of content available online. However, you have the option to dial back your deliver as required by different students, content, or other conditions. Unless there is a requirement to make certain elements of your class available online, you retain a lot of control here – 30% is not much and 79% is a lot.

Even using more recent definitions as Terry, Zafonte & Elliott (2018) said that blended learning is “defined as a class that meets 50-70% of the assigned class time in the face-to-face classroom setting and spends 30-50% of the assigned class time completing course work in a different setting.”

The average recommendation of 30% for independent work time online comes from high school online learning stakeholders (Peterson & Horn, 2016).

It is also fair to talk about what it means to make something available or delivered online. A substitution for a worksheet given in a face-to-face situation could be as rudimentary as a scan of the paper itself, upgrade if it is the digital copy of the worksheet, and the pinnacle is when you transform the worksheet questions into multiple online components (maybe in a Learning Management System, LMS). An example of this is to break the worksheet into these parts: a content/text page for background information, an interactive element such as pointing out to a webpage or having an activity for the students to complete online which provides immediate feedback in an entertaining and low-risk manner, a discussion are to help students through misconceptions or answer questions and then assessing (for a grade or not).

Choice within Online Content

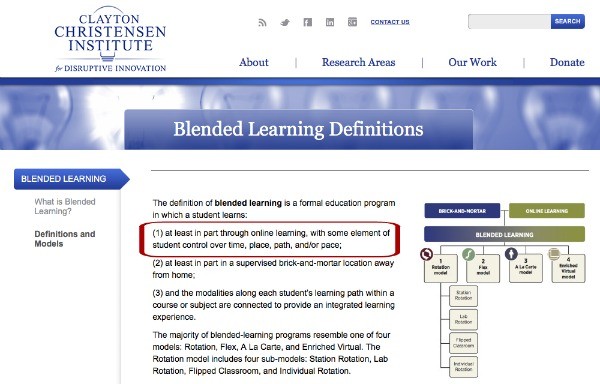

Another often referenced definer of Blended Learning is The Christensen Institute. Student control of Time, Place, and Path are important in this definition.

Path

Path implies there is a choice in what to do. Online content can offer choices in similar ways to face-to-face instruction. To meet this requirement, however, you need enough online content for students to choose between. I suggest building up projects first as they offer many ways to complete a project. One of the choices could walk a student how to propose an idea on how to complete the project to the teacher. Instead of looking for paths through every item, every day, start by offer choices in projects. A next step might be to use discussion boards to explore topics of interest for study. The element of the path still asks the content author to design multiple pieces of content for one assignment, but remember that online assignment can be the or one of the online elements.

Place

Place is a factor handled when online content is completed outside or inside the traditional classroom. Currently, most K12 schools include a predominance of on-campus activities. The key is to allow work to be submitted/completed asynchronous – that is work outside your “scheduled” teaching time and the “place” that you usually teach. The element of place requires the content author to offer more online work than what is required in a class, or accept that work within a range of time.

Time

Another element of the asynchronous nature of Blended Learning is the flexibility of time in relation to the number of time students have access to learning in the face-to-face environment. Sometimes related to pace, but a requirement for the asynchronous nature of Blended Learning itself.

Pace

Pace implies that students can take varying amounts of time to complete online content. Not even always the same rate either to make matters more complex. Examples for handling these differing rates of completing work are project contracts and choice units.

One way to accomplish this is to let the LMS do some of the heavy-lifting for you. Often LMSs offer ways to pre-assess, offer easy opportunities to resubmit improved work. Both of those tasks are difficult to successfully manage without technology, but with good knowledge of how your LMS works, you can offer re-teach and move-on-when-ready chances within your course.

This does require the content author to be more than just five minutes ahead of the “class,” because the class is in all different places. A strategy might be to create all of one item in advance, all Discussions, all Projects, all Assignments in advance. This might be better accomplished by splitting this up between more than one teacher, preferably a team you work closely with.

Looking at all these variables you can see why there are so many ways to offer online content via Blended Learning. By identifying the factors before you begin building online content and offering blending learning opportunities you will manage the expectations of all your stakeholders.

References

Allen, I. E., Ph.D., Seaman, J., Ph.D., & Garrett, R. (2007, March). Blending In The Extent and Promise of Blended Education in the United States. Retrieved May 04, 2019, from https://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/blending-in.pdf

Peterson, P. E., & Horn, M. B. (2016). The Ideal Blended-Learning Combination. Education Next, 16(2), 94–95.

Terry, L., Zafonte, M., & Elliott, S. (2018, August). Interdisciplinary Professional Learning Communities: Support for Faculty Teaching Blended Learning. International Journal of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education, 30(3), 402-411.

2021-09-21 at 12:53 pm

Amazing content! Blended learning offers both the instructor and the learners great flexibility. The golden rule is for the instructor to design for the best learning experience.

Davies recently posted…How to Build Leadership Capabilities for Successful Business Transformation